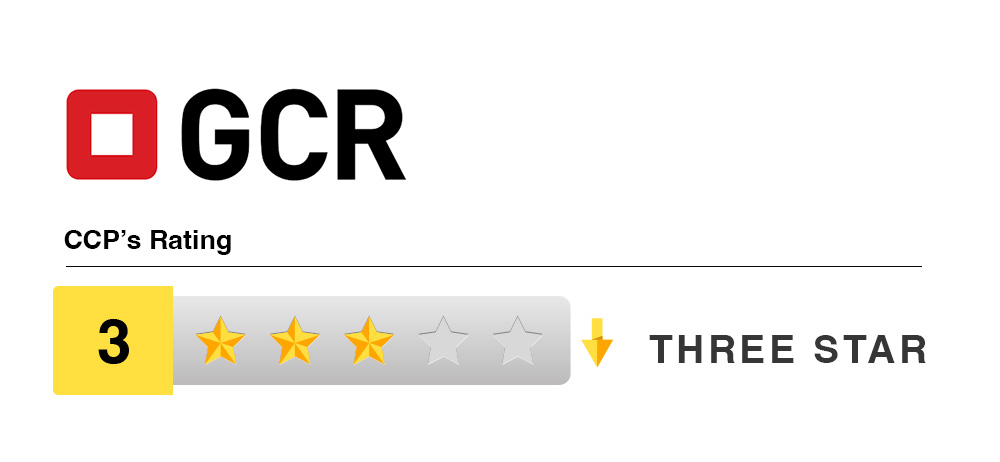

The Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) got back to work in 2015 after a tumultuous period of government transition and uncertainty over appointments prevented the authority from launching any new investigations.

It hit the ground running with a January raid against the national broadcasting association in conjunction with an investigation over the potential anticompetitive behaviour by the Pakistani Broadcasters Association.

Compared to 2014, the authority was able to initiate cases and pursue anticompetitive behaviour again, this time under the new leadership of Vadiyya Khalil. Khalil's immediate priority in 2015 was to "make up for lost ground," and she touted the commission's success with merger reviews and advocacy. Still, there were several ways the CCP underperformed last year.

Some practising lawyers had particularly scathing opinions about how the authority fared in 2015. One Pakistani lawyer blasted the CCP for becoming just another bureaucratic department, adding that it did not improve on prior years. "2015 saw more of the same as in 2014 with fewer investigations and more notices with no substantial impact on the economy or competition or consumer relief," the attorney said. Another took aim at the lack of ability to impose fines. Cartel fines were down last year - with the CCP only doling out €1.18 million in 2015 compared to the €61.2 million issued in 2013.

One attorney attributed this to the fact that the constitutionality of the authority has come under question over two key issues. The first issue is with regards to the jurisdiction of the CCP; there have been arguments in front of the High Court in Pakistan over whether the commission has the right to enforce competition law throughout the country, or if this should be left to provincial governments. Those arguing in support of the CCP claim that the country's interstate commerce clause gives enough power to the commission to act in a federal capacity.

The second issue also relates to the CCP's authority. The commission is clearly an executive body, yet has the ability to levy judicial fines-fines so harsh that one attorney said they could bankrupt a company. Pakistan has strict separation of powers, however, and some argue that only a judicial body should be allowed to dole out such fines.

All this matters for Rating Enforcement because while the High Court considers the constitutionality of the CCP, the authority has not been able to hand out fines. "As things stand, it's not a success story in Pakistan," the lawyer said, noting. "The state of competition law in Pakistan is extremely dire."

The same lawyer did say that the commission is able to conduct investigations and attract high-quality lawyers to work at the commission, with salaries competitive to the private sector. The lack of fines poses a significant hurdle, however. Because of the current inability to levy fines, cartels continue to operate - with one lawyer saying that there is a lack of competition in every industry, and another noting that some cartels remain as healthy as ever in Pakistan. While the CCP has targeted collusion in certain industries, it has not been able to eliminate the problem. "That raises the question of the efficacy of the commission's intervention," the lawyer said, also touching on the systemic failure that allows recipients of heavy fines - sometimes billions of rupees - to get a stay of the decision and let the case "gather dust" in the court system. Additionally, there remains no criminal track for antitrust violations.

Still, the lawyer praised the CCP, saying, "with each passing year, the commission has more to show for its efforts" as it expands its influence and reach.

Another area where the CCP has room for improvement is its lack of any PhD economists, and although there are employees with a background in law or economics, a lawyer said, "from a client perspective, one concern is the commission lacks sector specialists."

There are areas where the commission did extremely well compared to 2013, however. In 2015, the CCP conducted in-depth reviews of mergers on 68 occasions - compared to zero in 2013. The commission has managed to accomplish that with 33% less staff than two years ago, although the budget has increased in that time period. In December, the CCP approved the merger of three Pakistani stock exchanges with remedies to lessen the competition concerns.

There also seems to be a consensus that the commission remains a relatively open and transparent body compared to other areas of the Pakistani government. Ultimately the CCP has improved in some areas, but it remains constrained by systemic pressures. In order for the authority to truly do its job, one lawyer said, it needs to be detached from the executive and given some independence and autonomy to go after the "big fish without fearing for its own survival."